Bibliography / texts / A Regra do Jogo

To see the installation click here

A Regra do Jogo

As esculturas de Vasco Futscher apresentamse como peças de um jogo. Se o fossem, rapida mente perceberíamos tratarse de um estranho jogo. Os movimentos das peças foram feitos antes da nossa entrada no espaço (sabemos que não vão ser alteradas enquanto as contemplar mos mas não sabemos se o jogo acabou); e é um jogo sem tabuleiro (a superfície onde se mos tram não tem qualquer gra smo indicativo da sequência, orientação ou limite de movimento das peças). E ainda: peças de diferente cor e dimensão sucedemse, associamse e sobrepõem se sem que se possa descobrir uma regra para as suas deslocações (posições nais). Finalmente, há 3 diferentes cromatismos nestas peças e os grandes jogos de tabuleiro são, em geral, con frontos apenas de dois jogadores a que corres pondem duas cores opostas.

Mas podemos perceber que há regras gerais, cromáticas, numéricas, formais e de dimensão: três cores, três formatos e três tamanhos. Pode mos, portanto, supor que a regra de organiza ção das peças é, a nal, apenas uma regra estética capaz de estabelecer o seu arranjo no espaço e nunca destinada a representar uma vitória e uma derrota. Também reconhecemos a liação das formas escolhidas em certos cânones estabiliza dos da arte Clássica. A partir destes dados pode mos já aproximarnos da obra de Vasco Futscher.

Os volumes criados (citações de vasos, urnas ou bases escultóricas) desempenharam na linguagem clássica da construção uma função escultórica e/ou arquitetónica e tiveram um des tino prático e/ou decorativo. Mas, agora, cada um por si ou em conjunto, estes volumes são con cebidos contrariando toda a regra clássica. Por um lado, negamna, aproximandose da austeri dade e do arcaísmo de uma criação préclássica: modelagem rude ou tosca, secamente colori das, de cerâmica mas não vazadas – sin utilitas, en m. Por outro lado, exibem um excesso de presença, por repetição, desmultiplicação, densi cação de certas zonas.

O jogo de Vasco Futscher é continuar a quebra (moderna e pósmoderna) de toda a nor ma canónica antiga. A partir daqui aproximamo nos ainda mais da descodi cação da sua lógica de autonomia quer em relação ao modelo for mal quer ao modelo funcional do classicismo, do destino prático ou decorativo da cerâmica

e do destino estrutural ou decorativo dos ele mentos citados. Toda a sua obra anterior se desenvolveu, aliás, neste sentido tendo o seu trabalho em cerâmica (apenas iniciado em 2010) desenvolvido interrogações que já vinha fazendo em torno dos elementos decorativos da clássicos e pósclássicos, renascentista e bar roca. Assim, derivações criativas (não isentas

de alguma crítica e humor) de coruchéus e foga réus, de urnas e jarrões, de bases e capitéis ocu pam, quase por esta ordem, os seus anos de prá tica com material cerâmico. Importante será notar o carácter fragmentário de cada um dos elementos desenvolvidos, porque os primeiros são o culminar de certas estruturas de cobertura de edifícios ou balcões e varandas e as bases e capitéis necessitam de colunas para fazerem sentido estrutural e construtivo.

As peças apresentadas nesta exposição pertencem a uma fase nal de trabalho de maior depuração em que o artista se tem con centrado nas formas mais maciças e estáveis (bases) tornandoas autónomas isoladamente, em grupos ou em empilhamentos (colunas feitas de bases...). Regressando à obra em ques tão, percebemos, nalmente, que a organiza ção das peças no espaço tem, a nal, uma regra. Remete para o corpo, ao supor uma coreo gra a das peças em si e do espectador em redor das peças; e remete para o social, ao assumir uma hierarquia entre as peças. Mas, ao mesmo tempo é aberta e livre (pode conduzirnos mesmo ao caos) pois podemos adivinhar que

a solução apresentada pelo artista não será de nitiva – é possível que, noutro tempo no mesmo lugar ou noutro tempo noutro lugar, haja soluções diversas para este mesmo agru pamento de peças. A regra decisiva é, portanto, plástica e visual, estética: considera o particular (cada forma, cada dimensão, cada cor) e o todo; e considera o tempo e a multiplicação das pos sibilidades ao criar uma instalação (um campo de esculturas) que, permanecendo estática, é modificada no presente pelos movimentos que realizamos em seu redor e, no futuro, pelas novas soluções de composição que vierem a ser encontradas.

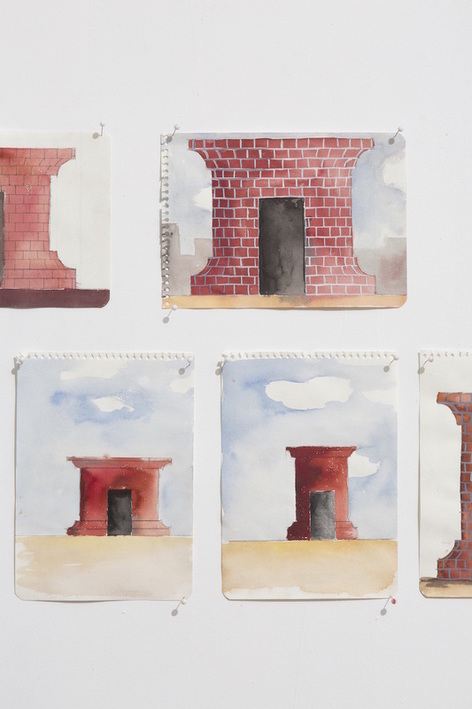

Finalmente, podemos ainda desenvolver uma especulação fundamentada em estudos (desenhos e maquetas à escala) que ocupam algumas paredes e prateleiras do atelier de Vasco Futscher. A de que ele se aproxima agora de uma ambição maior: considerar a forma de cada base como maqueta de um edifício que, a ser construído (em tijolo modelado e cozido por si), con guraria a função simbólica de um enorme forno ou cenotá o circulares e colo carnosia, de novo, na linha de numa citação clássica: a da utópica do neoclassicismo francês.

João Pinharanda

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Rules of the Game

Vasco Futscher’s sculptures are presented as pieces of a game. If they were really that, we would quickly discover it to be a strange game: the pieces were moved before we entered the space (we know they are not going to be moved while we are looking at them, but we do not know if the game is over); and it is a game with out a board (the surface on which they are shown has no graphic signs indicating sequence, orientation or limits to the movement of the pieces). More still: pieces of different sizes and colors follow one another, associate and over lap each other and make it impossible for us to deduce any rule governing their movements (their nal positions). Finally, the pieces come in three colors, contrasting with most board games, which are commonly disputed by two players, and with two opposing colors.

We can, however, recognize some general rules determining their chromatic, numerical, formal, and size relations: three colors, three for mats, and three sizes. We can therefore assume that the rule governing these pieces is just one aesthetic rule that de nes their disposition in space but does not allow any representation of victory or defeat. We also recognize the liation of these forms in certain canons of Classic art. Using these elements, we can start to understand this work by Vasco Futscher.

These volumes (quoting vases, urns, pedes tals or plinths), had a sculptural and/or archi tectonical role in the classical language of con struction, with their functional or decorative functions. But now, individually or in their en semble, these volumes are produced in disre spect of all classical norms. In the one hand, they refuse them, approaching the austerity and the archaism of a preclassic construction: crude or coarse modeling, dryly colored, ceramic but not hollow – sin utilitas. On the other hand, they reveal an excess of presence through a process of repetition, multiplication, and densi cation of certain areas.

Vasco Futscher’s game is the furtherance of the (modern and postmodern) break from all old canons. From here, we are even closer to the decoding of his logic of autonomy from

the formal and functional models of classicism, from the practical and decorative functions of ceramics and the structural or decorative role of the quoted architectonic elements. All his pre vious works were developed in this same direc tion, and his ceramic works (starting in 2010) only advance his questioning of the decorative elements of classical, postclassical, renais sance and baroque architecture. Creative deri vations (often humorous and critical) of spires, cressets, urns and jars, plinths and capitals, almost by this order, are the central themes of the years the artist has dedicated to ceramic works. It is important to note the fragmentary character of each one of these elements: if the rst are used at the top of certain structures that cover buildings or verandas, plinths and capitals need columns in order to make some kind of structural sense.

The pieces presented in this show belong to a later and more speci c phase of the artist’s work, as he focuses on bulkier and rmer shapes (plinths) and makes them autonomous, either individually, in groups, or in stacks (col umns made from stacked plinths). Going back to the work the artist presents in this exhibition, we nally understand that the distribution of the pieces in space follows one rule. It refers to the body, as it implies a choreography of the pieces, and of the spectators moving around the pieces; and it refers to the social, as it assumes

a hierarchy between the pieces. But, at the same time, it is open and free (even chaotic) because it allows us to assume that the solution here pres ented is not de nitive – it is possible that, at some other time, in this or in another place, different solutions will be found for this same group of pieces. The fundamental rule in this game is plastic, visual, and aesthetic: it considers the singular (each volume, each color), and the whole, it considers time and the multiplication of the possibilities as it creates an installation

(a eld of sculptures) that, being static, changes in the present as we move our bodies through it, and will change in the future as new composi tional solutions are discovered or found for it.

Finally, and based on the studies (drawings and scale models) we found on Vasco Futscher’s studio walls and shelves we can speculate that he is on the verge of ful lling an even bigger ambition: seeing the shape of each plinth as the model for a building that, once built (in bricks molded and baked by the artist) would con gure the symbolic function of an enormous circular oven or cenotaph, confronting us once more with an evocation of the classical: the utopic architec ture of French neoclassicism.

João Pinharanda

To see the installation click here

A Regra do Jogo

As esculturas de Vasco Futscher apresentamse como peças de um jogo. Se o fossem, rapida mente perceberíamos tratarse de um estranho jogo. Os movimentos das peças foram feitos antes da nossa entrada no espaço (sabemos que não vão ser alteradas enquanto as contemplar mos mas não sabemos se o jogo acabou); e é um jogo sem tabuleiro (a superfície onde se mos tram não tem qualquer gra smo indicativo da sequência, orientação ou limite de movimento das peças). E ainda: peças de diferente cor e dimensão sucedemse, associamse e sobrepõem se sem que se possa descobrir uma regra para as suas deslocações (posições nais). Finalmente, há 3 diferentes cromatismos nestas peças e os grandes jogos de tabuleiro são, em geral, con frontos apenas de dois jogadores a que corres pondem duas cores opostas.

Mas podemos perceber que há regras gerais, cromáticas, numéricas, formais e de dimensão: três cores, três formatos e três tamanhos. Pode mos, portanto, supor que a regra de organiza ção das peças é, a nal, apenas uma regra estética capaz de estabelecer o seu arranjo no espaço e nunca destinada a representar uma vitória e uma derrota. Também reconhecemos a liação das formas escolhidas em certos cânones estabiliza dos da arte Clássica. A partir destes dados pode mos já aproximarnos da obra de Vasco Futscher.

Os volumes criados (citações de vasos, urnas ou bases escultóricas) desempenharam na linguagem clássica da construção uma função escultórica e/ou arquitetónica e tiveram um des tino prático e/ou decorativo. Mas, agora, cada um por si ou em conjunto, estes volumes são con cebidos contrariando toda a regra clássica. Por um lado, negamna, aproximandose da austeri dade e do arcaísmo de uma criação préclássica: modelagem rude ou tosca, secamente colori das, de cerâmica mas não vazadas – sin utilitas, en m. Por outro lado, exibem um excesso de presença, por repetição, desmultiplicação, densi cação de certas zonas.

O jogo de Vasco Futscher é continuar a quebra (moderna e pósmoderna) de toda a nor ma canónica antiga. A partir daqui aproximamo nos ainda mais da descodi cação da sua lógica de autonomia quer em relação ao modelo for mal quer ao modelo funcional do classicismo, do destino prático ou decorativo da cerâmica

e do destino estrutural ou decorativo dos ele mentos citados. Toda a sua obra anterior se desenvolveu, aliás, neste sentido tendo o seu trabalho em cerâmica (apenas iniciado em 2010) desenvolvido interrogações que já vinha fazendo em torno dos elementos decorativos da clássicos e pósclássicos, renascentista e bar roca. Assim, derivações criativas (não isentas

de alguma crítica e humor) de coruchéus e foga réus, de urnas e jarrões, de bases e capitéis ocu pam, quase por esta ordem, os seus anos de prá tica com material cerâmico. Importante será notar o carácter fragmentário de cada um dos elementos desenvolvidos, porque os primeiros são o culminar de certas estruturas de cobertura de edifícios ou balcões e varandas e as bases e capitéis necessitam de colunas para fazerem sentido estrutural e construtivo.

As peças apresentadas nesta exposição pertencem a uma fase nal de trabalho de maior depuração em que o artista se tem con centrado nas formas mais maciças e estáveis (bases) tornandoas autónomas isoladamente, em grupos ou em empilhamentos (colunas feitas de bases...). Regressando à obra em ques tão, percebemos, nalmente, que a organiza ção das peças no espaço tem, a nal, uma regra. Remete para o corpo, ao supor uma coreo gra a das peças em si e do espectador em redor das peças; e remete para o social, ao assumir uma hierarquia entre as peças. Mas, ao mesmo tempo é aberta e livre (pode conduzirnos mesmo ao caos) pois podemos adivinhar que

a solução apresentada pelo artista não será de nitiva – é possível que, noutro tempo no mesmo lugar ou noutro tempo noutro lugar, haja soluções diversas para este mesmo agru pamento de peças. A regra decisiva é, portanto, plástica e visual, estética: considera o particular (cada forma, cada dimensão, cada cor) e o todo; e considera o tempo e a multiplicação das pos sibilidades ao criar uma instalação (um campo de esculturas) que, permanecendo estática, é modificada no presente pelos movimentos que realizamos em seu redor e, no futuro, pelas novas soluções de composição que vierem a ser encontradas.

Finalmente, podemos ainda desenvolver uma especulação fundamentada em estudos (desenhos e maquetas à escala) que ocupam algumas paredes e prateleiras do atelier de Vasco Futscher. A de que ele se aproxima agora de uma ambição maior: considerar a forma de cada base como maqueta de um edifício que, a ser construído (em tijolo modelado e cozido por si), con guraria a função simbólica de um enorme forno ou cenotá o circulares e colo carnosia, de novo, na linha de numa citação clássica: a da utópica do neoclassicismo francês.

João Pinharanda

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Rules of the Game

Vasco Futscher’s sculptures are presented as pieces of a game. If they were really that, we would quickly discover it to be a strange game: the pieces were moved before we entered the space (we know they are not going to be moved while we are looking at them, but we do not know if the game is over); and it is a game with out a board (the surface on which they are shown has no graphic signs indicating sequence, orientation or limits to the movement of the pieces). More still: pieces of different sizes and colors follow one another, associate and over lap each other and make it impossible for us to deduce any rule governing their movements (their nal positions). Finally, the pieces come in three colors, contrasting with most board games, which are commonly disputed by two players, and with two opposing colors.

We can, however, recognize some general rules determining their chromatic, numerical, formal, and size relations: three colors, three for mats, and three sizes. We can therefore assume that the rule governing these pieces is just one aesthetic rule that de nes their disposition in space but does not allow any representation of victory or defeat. We also recognize the liation of these forms in certain canons of Classic art. Using these elements, we can start to understand this work by Vasco Futscher.

These volumes (quoting vases, urns, pedes tals or plinths), had a sculptural and/or archi tectonical role in the classical language of con struction, with their functional or decorative functions. But now, individually or in their en semble, these volumes are produced in disre spect of all classical norms. In the one hand, they refuse them, approaching the austerity and the archaism of a preclassic construction: crude or coarse modeling, dryly colored, ceramic but not hollow – sin utilitas. On the other hand, they reveal an excess of presence through a process of repetition, multiplication, and densi cation of certain areas.

Vasco Futscher’s game is the furtherance of the (modern and postmodern) break from all old canons. From here, we are even closer to the decoding of his logic of autonomy from

the formal and functional models of classicism, from the practical and decorative functions of ceramics and the structural or decorative role of the quoted architectonic elements. All his pre vious works were developed in this same direc tion, and his ceramic works (starting in 2010) only advance his questioning of the decorative elements of classical, postclassical, renais sance and baroque architecture. Creative deri vations (often humorous and critical) of spires, cressets, urns and jars, plinths and capitals, almost by this order, are the central themes of the years the artist has dedicated to ceramic works. It is important to note the fragmentary character of each one of these elements: if the rst are used at the top of certain structures that cover buildings or verandas, plinths and capitals need columns in order to make some kind of structural sense.

The pieces presented in this show belong to a later and more speci c phase of the artist’s work, as he focuses on bulkier and rmer shapes (plinths) and makes them autonomous, either individually, in groups, or in stacks (col umns made from stacked plinths). Going back to the work the artist presents in this exhibition, we nally understand that the distribution of the pieces in space follows one rule. It refers to the body, as it implies a choreography of the pieces, and of the spectators moving around the pieces; and it refers to the social, as it assumes

a hierarchy between the pieces. But, at the same time, it is open and free (even chaotic) because it allows us to assume that the solution here pres ented is not de nitive – it is possible that, at some other time, in this or in another place, different solutions will be found for this same group of pieces. The fundamental rule in this game is plastic, visual, and aesthetic: it considers the singular (each volume, each color), and the whole, it considers time and the multiplication of the possibilities as it creates an installation

(a eld of sculptures) that, being static, changes in the present as we move our bodies through it, and will change in the future as new composi tional solutions are discovered or found for it.

Finally, and based on the studies (drawings and scale models) we found on Vasco Futscher’s studio walls and shelves we can speculate that he is on the verge of ful lling an even bigger ambition: seeing the shape of each plinth as the model for a building that, once built (in bricks molded and baked by the artist) would con gure the symbolic function of an enormous circular oven or cenotaph, confronting us once more with an evocation of the classical: the utopic architec ture of French neoclassicism.

João Pinharanda